Florida

Once entirely covered by the ocean, Florida today sits atop a limestone plateau that is pocketed with a variety of karst features and terrain. The porous nature of Florida’s underlying geology coupled with the explosive population growth over the last 50 years has placed increased pressure on our groundwater supply, water quality, and species found in the aquifer. Despite the broad geographic range that the Floridan aquifer covers, pollution from stormwater runoff, agriculture, livestock, impacts from recreation, problems associated with invasive species, and groundwater consumption are just a few of the problems that endanger the habitat of springs and caves.

Florida is the 22nd largest state (in terms of area) in the United States, and is bordered by both the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico. Comprised of 58,560 square miles of land, Florida is also home 11,000 miles of streams, rivers, canals, and waterways. Geologists estimate that there are more than 700 springs in Florida, representing the largest concentration of freshwater springs on Earth. Spring waters discharge from the Floridan aquifer – one of the most productive in the United States – and exhibit a wide range of hydrology and water chemistry. Of these 700+ springs, approximately 33 are first magnitude springs with discharge rates exceeding 64.6 million gallons per day. It is estimated that while 30% of these springs are located on conservation lands, approximately 65% are still in private ownership.

Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission Invasive Plant Biologist Nathalie Visscher with water lettuce, an invasive exotic aquatic plant that responds to nutrient loading and quickly clogs rivers and lakes, reducing oxygen, water flow, and habitat quality for wildlife.

More than 1,094 square miles of land in Florida are designated for livestock use, and over 400,000 tons of animal waste enters our groundwater annually. This influx of nutrients can disrupt the water chemistry necessary for maintaining healthy plant and animal communities in springs and caves. In addition, the excessive nutrients stimulate the growth of exotic plants, which outcompete native vegetation for space, light, and nutrients, ultimately affecting the native faunal food chain.

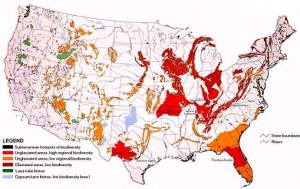

The biology and ecology of Florida’s springs and associated cave systems have not been well studied, though they are thought to include some of the most biological diverse karst areas in the United States. In fact, Florida karst systems contain among the most diverse aquatic faunas nationwide. Unfortunately, as population density in the recharge areas above the aquifer has increased, the quality of the groundwater has declined, and the organisms associated with the springs and cave systems have been negatively affected.

Biodiversity levels of karst landforms in the U.S. Published by David Culver and the World Wildlife Fund. Figure, courtesy of David Culver.